I am still so smitten by baseball. I’m not, however, very excited for the future of the game. My plan was to pen and publish a critical homage to commemorate Opening Day last year. But Opening Day came and went and I had already moved on to other things.

I so adored my father. He never told me outright but I know he loved me. And I know he was proud of me though, again, he never told me outright. He was, however, how and why I am still so smitten by baseball. My plan was to pen and publish an homage to our relationship for Father’s Day last year. But Father’s Day came and went and I had already moved on to other things.

So before I move on to other things once again, I thought it might make sense to combine baseball and my father just to see what emerges, since the story for me begins with the fact that I could never separate the two in the first place. Not just because my father’s primary job was to write baseball. But because — like every other top baseball writer back in the 40s, 50s and 60s — the boy in him couldn’t imagine anything better: liquor, smokes and jokes among hard drinking, hard smoking, hard joking professional storytellers — all of whom congregated in the press box directly behind home plate each and every game day. Best seats in the house for the best storytellers, the real boys of summer. “What could be better?” he asked himself one day in his youth. “Nothing,” came the reply from a deeper place. So from his lips to God’s ear…

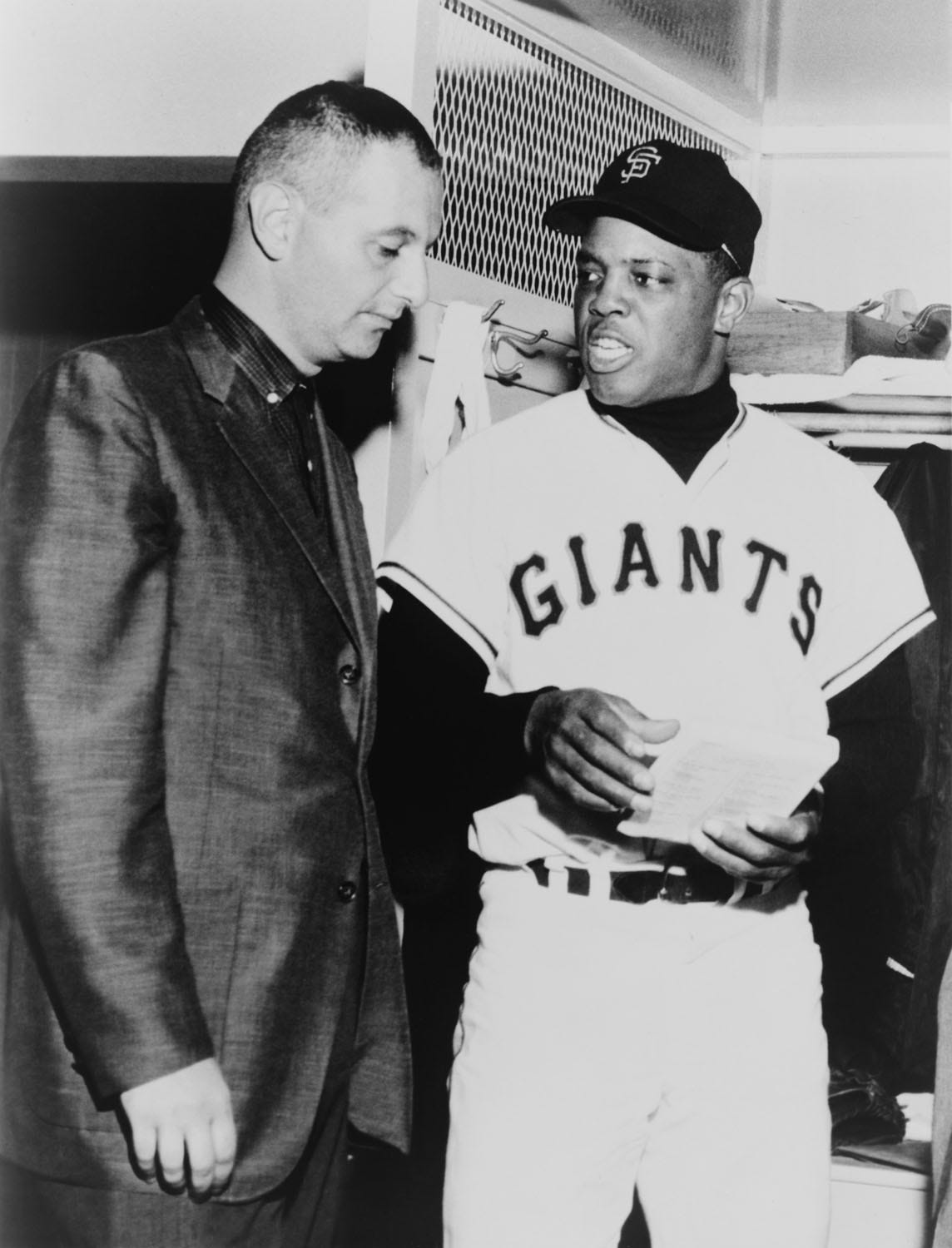

My father was 25 years old when he hitched his star to Willie Mays of the New York Giants in 1951, Willie’s rookie year. Close to God as my father ever got, I think. Pretty close in any event, all things considered — at least through my eyes, the ones I inherited. He moved the family out west to Mill Valley just north of the Golden Gate when the Giants moved west in the late 50s. Couldn’t bear the separation from Willie is how I explain the move to those who ask. So my brothers and I grew up watching Willie Mays play baseball for the San Francisco Giants at Candlestick Park, perhaps the world’s worst place to watch history’s greatest ballplayer.

The August chill of Candlestick Park notwithstanding, baseball and Willie fit the contours of my father’s sensibilities like an old broken-in mitt. Just enough redolence of youth to stay forever young when nestled deep in its pocket. Just enough youthful freedom and arrogance to patrol vast pastures of outfield grass. Just enough explosive speed and innate talent to chase down dreams like line drives to the gaps. If my father couldn’t be a Willie Mays, then he could at least find one and write about him. So from his lips to God’s ear…

All creation is a function of rhythm — and all artists create by ear. Painters paint by ear. Sculptors sculpt by ear. Writers write by ear. I learned this lesson first from the times I would visit my father between innings in the press box. Back then, back in the early 1960s, a young boy of ten or twelve could patrol the bowels of a major league ballpark alone with fearless abandon — and sheer wonder. No one ever stopped me back then because no one worried about a boy wandering alone at a ballpark. After all, what relationship could be more natural or symbiotic than a young boy and a ballpark?

The rewards of such intrepid solo journeys were manifest always: the intoxicating colognes of cigarette smoke, ballpark franks and roasted peanuts; how the cool concrete of the grandstands opened at each section to permit truncated glimpses of the outfield grass, aglow like precious emeralds under the lights or the midday sun. The exact same rewards still await me now in my seventies each time I visit a ballpark. The playing field still opens before me like a cathedral, and still awakens in me the same childhood awe and wonder, like some pavlovian reminder of freer times. Or perhaps, at this more advanced stage of my life, just the ignorant bliss of limbic oblivion.

All creation is a function of rhythm — and all artists create by ear. The door to the press box was heavy, more I think now to keep the dysfunctional baseball writers inside than to keep less-dysfunctional fans out. Once disturbed from its jam it all but blew open in violent relief from the combustive mix of bourbon and tobacco it trapped inside like the industrial secret it concealed: Back then, you see, many more avid baseball fans read about the game in the newspaper each morning than watched it at the ballpark the day before.

Down the aisle within, through the gray-purple haze of smoke, emerged a Mt. Rushmore of great working writers adrift in distraction but tethered by deadlines for stories about a game with no clock. Laughter and expletives and astonished acclaim in the days before instant replay in Ultra HD slo-mo fucked with memory. Take the next few seconds between pitches to wonder out loud. Did we really see what we just saw? Another toast to Marichal or Koufax or Gibson or Clemente or Aaron or Mays. Especially Mays. The constant clatter of typewriters suspended for the moment by the telltale crack of bat on ball, loud enough five stories up in the mezzanine to pierce the late-inning din of the crowd and ignite a roar that exploded between our ears and shook the grandstands.

All creation is a function of rhythm — and all artists create by ear. Art prevailed daily in the cacophony and chaos of the pressbox despite the Dali-esque clock of constant distraction. The very best among those who populated the aisle on any given day, I learned, were those who could suspend life and laughter and tears long enough in real time to hear and respond to their own internal rhythms, muses, demons and devils. Back then, back before the great migration from print to broadcast, those who could pierce the collegial delirium to find and re-establish the rhythm, and do it often enough over decades to raise a family, were working-class heroes. At least to me. As wondrous and prolific and accomplished as my father was over the course of his career, his greatest achievement — in my heart and mind — was that he raised four kids with my mom and remained married to her until she passed from cancer in 1989.

The joyous confluence of baseball and my father taught me how to listen to the silence between pitches. The errant notes always announce their true intent when they interrupt the rhythm. Go back, they tell us. Try again. Try harder…

Opening Day to the Mill Valley Little League season was a festive rite of spring each year. The whole town turned out for the parade of teams that assembled first on Throckmorton Avenue near Old Mill Park, verdant in the sweet morning air and cool shade of redwoods and pines, then meandered like a coral snake with riotous bands of color past the lazy old one-room bus depot downtown, up the rise to the Sequoia Theater, east along Blithedale Avenue to the small post office, turning north before arriving finally at Boyle Park where the outfield fences, concession stands and bleachers were waiting — festooned with red, white and blue bunting.

There, town officials, bands, dignitaries and clergy welcomed and blessed us. Like all the other young ballplayers in town, my brothers and I marched each year in our team uniforms (provided by Campbell Bishop Chevrolet). Pomp and circumstance of any sort always discomforts me, but marching in the parade was an obligation of sorts, one way we marked the passage of time back in the late 1950s and early 60s. Little League baseball was one of the few family traditions my parents — baptized in liberal secularism at the University of Chicago as teenagers during World War II — allowed us and themselves. We were, afterall, a baseball family in a small American town.

Two games a week we played for a couple of months into the summer. On game days, my mom volunteered to run the concessions with other moms while the dads coached or paced or heckled the umpires. Red and black licorice twists sold for a few pennies apiece. Sodas served in red and white Coca-Cola cups for a dime. Hotdogs, steamed and wrapped, for a quarter. Families with young children congregated around picnic tables just across the heavy wood walking bridge that spanned Boyle Creek behind the grandstands on the first-base side of the playing field. After a few seconds in flight, an occasional foul ball would christen the hood of a parked car behind the grandstands along the third-base line with an unmistakable…wait for it…wait for it…thunk! “Oooooh!” came the response from the grandstands.

I remember everything about the very first time I hit a baseball hard. I remember exactly how my swing drove in the winning run of the Peewee League championship game. I remember the name of the pitcher (I wonder if he still remembers mine). I remember the sound of the ball against my bat, the delicious and unmistakable tactile sensation as the moment moved from the bat into my hands and wrists, up my arms and shoulders and into the official scorebook. I remember just rounding second base after the winning run had already scored as my father sprinted across the third base line to scoop me up in his arms.

My older brother Mike was always the star athlete in the family. My oldest brother Dave and I had our moments on the field, but Mike was the undisputed star. His final year in Little League was a dream season with multiple no-hitters on the mound and league-crushing offensive numbers in the box. It all ended sadly, however. Mike's elbow blew out in the last regular-season game. He kept it to himself, but he was clearly in serious pain back on the mound for the championship game a week later. His fastball, once the stuff of local legend, was suddenly pedestrian, his curve flat, and he got hammered. My father and the team manager refused to pull him despite his obvious pain. I was playing first base at the time, heartbroken to witness his public fall from grace. But baseball — like freedom — doesn't reward promise or yesterday’s stats. Like life, it will always find your weakness.

A few years later my father authored a small tome, How to Coach, Manage, and Play Little League Baseball: A Commonsense Instructional Manual, published by Simon and Schuster. It was, of course, an act of love and contrition — to my knowledge the only little league how-to book ever published with a Forward by Willie Mays.

Throughout little league, pony league and high school ball, my father attended almost every game Mike and I ever played. Mike went on to play thousands of senior-level softball games as an adult in Hawaii, and more recently coached a nationally ranked amateur hardball team in Michigan City, Indiana, where he still pitches and takes batting practice, weather permitting. After two surgeries thirty years apart, his elbow is all but bionic now, and he still throws a heavy ball that cracks the pocket of your glove and pushes you back like a 12-gauge recoil.

As for me, I had one brief flirtation with actual prowess on the field as a sophomore in high school. Always a decent first baseman, I started the season that year, it seemed, with new eyes, suddenly predatory and rapacious. I was squaring up on the ball and tagging long drives with every at bat, hitting .667 when I ruptured the ACL in my right knee out at first base. My glory on the field may have been short-lived, but it liberated me for a lifetime.

Sidebar: Brother Mike played Little League and Pony League with Willie’s hand-me-down glove. As a lefthander I played first base in Little League through high school with Willie McCovey’s old glove. Willie Mac’s glove weighed a ton and threatened to swallow me whole every time I slipped my hand into it. But it always felt and smelled like summer to me. Now in our seventies, neither Mike nor I can remember what the hell happened to those gloves. Of course, these days we can’t remember what we had for dinner last night, either. But it was pretty cool at the time.

On his 50th birthday my dad was awarded a gold-plated lifetime press pass from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. I’m told only a handful are issued to each generation. But because no one in security at the ballparks has ever actually seen one, his gold-plated lifetime press pass entitled him only to get thrown out of every ballpark in the country. Quite the honor nonetheless.

My daughter Cayla played organized softball, first in Forest Hills, Queens, then for Bronx Science in high school. I was always either in the dugout or in the stands to cheer her on. There’s a long-standing tradition in my family, a rite performed when the father takes his child to her first major league ballgame. Cayla’s first was the Mets versus the Pittsburghs at Shea Stadium in Flushing. She was six years old at the time. Comes the seventh-inning stretch, I stand up right before everyone else. “Watch this,” I say to Cayla, raising my arms. The entire crowd stands up in response. “Now watch this,” I tell her. I wave my arms like a philharmonic conductor whereupon the whole stadium breaks into song. The look on her face was magical, now a memory worth lifetimes. Of course it’s easy to bamboozle a first grader. But you can only get away with this tradition once per child, and Cayla’s the only one of mine — as far as I know. Sometimes once is enough.

The great journalists of the metro daily newspapers begat the legends of Hollywood and baseball throughout the first six decades of the 20th century. By comparison, TV and the Internet can only confer celebrity and stardom. My father, a baseball historian and old-school journalist, passed away in 2007 at the age of 80. I was with Cayla when I got the call from Mike. She was only seven years old. She said later that it was the only time she saw me cry.

Mike and I still talk baseball with endless wonder over the phone virtually every morning, in-season and out. Cayla and I talk baseball every week as well. I’m most happy to report that her love for the game seems every bit as deep and unwavering as mine and Mike’s. Happy and gratified also that her excitement for the future of the game eclipses mine at a time when hope for the future is in such short supply. Thanks, Dad. From your lips to God’s ear…